Most Role-Playing Games resolve conflicts with dice. But since we have a Space·Time Deck at hand (or any other kind of Tarot-like Deck), let’s see if we can use it to bring about a different manner of resolving conflicts.

About Conflicts

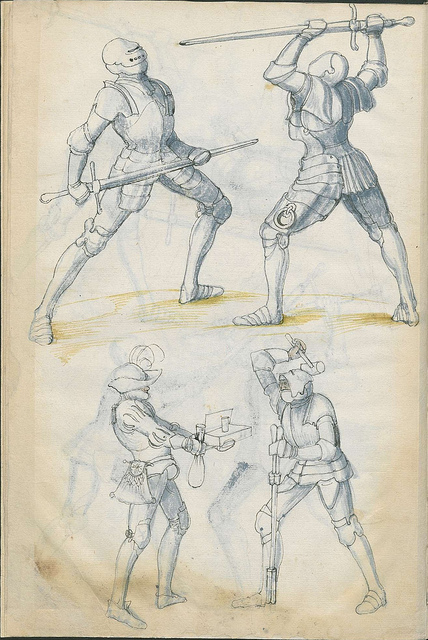

A Conflict is a scene in which two parties or more have agendas, which cannot be fulfilled simultaneously. In most role-playing games, the most common form of conflict is the combat, but that is by no mean the only form possible: conflict could be car races, social wit, political campaigns, chess, battlefield strategy, attempting to ruin your opponent’s reputation or fortune, popularity contests, football matches, etc.

Conflict does not have to be symmetrical. A guerilla may be attempting to cause maximal damage to infrastructure while the government forces attempt to destroy the guerilla forces. An outlying party may be attempting to propagate its doctrine while the more traditional parties attempt to maintain the status quo. A sniper may attempt to kill a target. A child may be attempting to attract attention during a kidnapping attempt.

Conflicts assumes that both parties have some manner of assessing their situation, and have some ability to act. In other words, as long as the target of the sniper is not aware of the sniper, there is no conflict between the sniper and the target. In other words, if no other factors are in play, the act of sniping will most likely be a simple case of Overcoming an obstacle. On the other hand, if the target is running away, there is a – very asummetrical — conflict between the sniper and the target. Similarly, if an enemy patrol is currently looking for an infiltrator, there is a conflict between the sniper’s smarts, stealth and sniping ability and the enemy patrol’s smarts and detection ability. Similarly, if the traditional parties are busy quelling a political crisis or are unaware of the outlying party, there is no conflict between the outlying party and the traditional parties – although there could be a conflict between the outlying party and a specific candidate.

Conflicts decide whether any of the parties manage to reach their desired outcome. In the case of a race, the desired outcome is typically arriving first. In the case of a gang fight, the desired outcome is typically getting the other gang to end up broken and bleeding or fleeing. In the case of a sniper vs. patrol, the desired outcome is typically evading the patrol and killing the target vs. capturing the intruder before he has the chance to cause damage. The players representing each party must have a clear idea of the desired outcome for the conflict.

They are, of course, entirely free to change the desired outcome, but this may end up completely changing the state of the conflict. For instance, if the hidden sniper finds themself cornered, they may decide to change plan, create maximum chaos and attempt to escape – but that’s a new conflict.

The following conflict resolution mechanics are, by design, as minimal as possible. They assume that the players already know how to estimate the difference of strengths between the parties in a conflict.

Setting up Conflict

Before the Conflict starts, the Table needs to:

- Agree that the scene is a Conflict.

- Determine the Parties involved.

- Determine the Desired Outcomes.

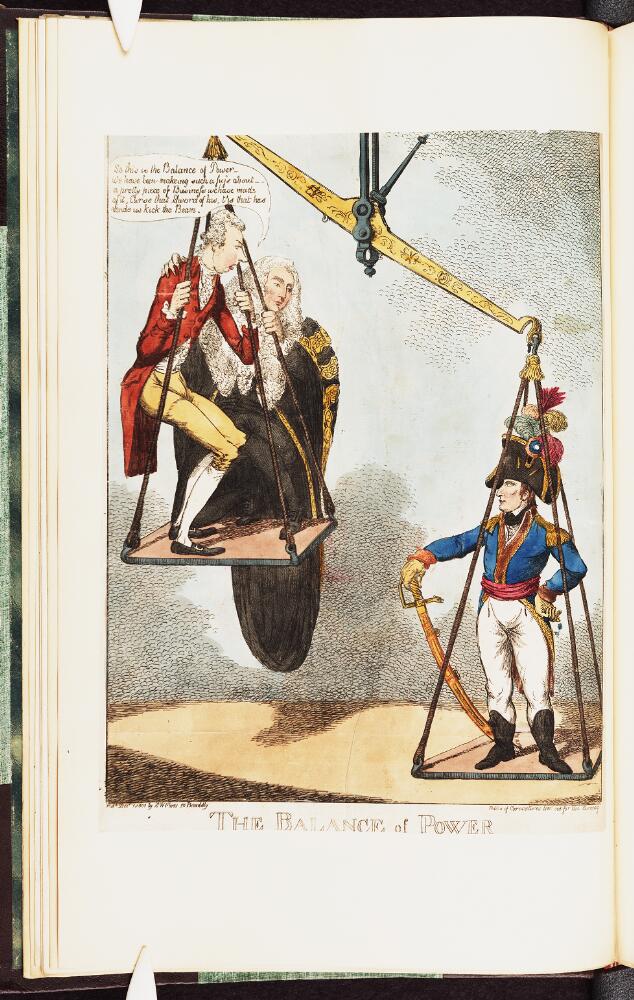

- Determine the initial Balance of the Conflit. It may be either

- Balanced – while the parties may be widely different, they have roughly the same chances of succeeding.

- Unbalanced – one party has a strong advantage.

- Overwhelming – one party is nearly certain of victory.

We do not cover this last point – it is left up to the Table, depending on how each Party is defined.

Resolving a Conflict

Conflict Resolution takes place in rounds. Rounds do not have a specific duration. One round may last a few seconds while the next one lasts several months - as long as it makes sense in-story.

Each Round starts with each party describing broadly their current tactics to reach their Desired Outcome.

The Round will let the Table determine:

- which party, if any, has advanced towards their Desired Outcome;

- how it happened;

- whether the Conflict continues, stops entirely or changes shape.

Drawing cards

- If the Conflict is Balanced

- Each side picks a card of the Space·Time Deck.

- If the Conflict is Unbalanced

- The advantaged side draws two cards.

- Each disadvantaged side draws one card.

- If the Conflict is Overwhelming

- The advantaged side draws two cards.

- Each disadvantaged side also draws two cards.

Once drawn, cards are visible.

Establishing the flow

- If any of the cards drawn is the Excuse

- The Balance of Conflict moves towards Balanced:

- Balanced -> Balanced

- Unbalanced -> Balanced

- Overwhelming -> Unbalanced

- Discard the Excuse and draw another one for narration purposes.

- The Balance of Conflict moves towards Balanced:

- Otherwise, if the Conflict is Balanced

- If the card of a party beats the card of all other parties, the Balance moves in favor of the winning party

- Balanced -> Unbalanced

- Otherwise, the round is a stalemate, the Balance does not change

- If the card of a party beats the card of all other parties, the Balance moves in favor of the winning party

- Otherwise

- If, for every one of the disadvantaged parties involved, there is one card of the advantaged side and one card of the disadvantaged side such that the the advantaged side wins, the Balance moves in favor of the side that is already advantaged

- Balanced -> Unbalanced

- Unbalanced -> Overwhelming

- Overwhelming -> Victory

- If, for every one of the disadvantaged party involved, all the combinations of one card of the advantaged side

and one card of the disadvantaged side imply that the advantaged side loses, the Balance moves towards Balanced

- Unbalanced -> Balanced

- Overwhelming -> Unbalanced

- Otherwise, the Balance remains unchanged.

- If, for every one of the disadvantaged parties involved, there is one card of the advantaged side and one card of the disadvantaged side such that the the advantaged side wins, the Balance moves in favor of the side that is already advantaged

Narrating the outcome of the round

At this stage, each side knows whether their tactics have succeeded or failed. The cards that they have drawn will answer the Question: How did my tactics succeed? or How did my tactics failed?.

As usual, the player who drew the card picks the Answer and the Facts. If the players decides to interpret the card as meaning that reinforcements are coming, or that a mysterious deity has blessed that quest, this is entirely acceptable, as long as it makes sense with the Facts that have already been established – so no deity in a Film Noir set in our world’s 1920s, no reinforcements if you are the last human alive. If playing with a GM, the GM is the ultimate responsible for maintaining consistency and Facts has the power to veto any description if it causes a contradiction.

As usual, this freedom does not extend to one side dictating what other sides have been doing. In other words, if you narrate that you have been dodging bullets from the Undead Marines, the player in charge of the Undead Marines may overrule the sentence and inform you that no, the Undead Marines were launching grenades or were busy attempting experimenting with vodka to see if they still could get drunk.

Within these limitations, the player who drew the card has full narrative authority. Again, the player is expected to interpret the cards but only the player can decide on the actual interpretation. This may mean that players will come up with uninteresting interpretations from time to time. That’s ok.

Deciding whether the Conflict continues

If any side reached Victory, the Conflict is over, congratulations, that side’s Desired Outcome has been reached.

Otherwise, any side may decide to stop the Conflict. This may represent a concession of defeat, such as a thief escaping the scene empty-handed before being caught. This may represent a postponed Conflict, such as two duelling enemies being forced to hide their weapons and bid each other farewell to avoid the police. This may represent a party Reformulating the Conflict, as would be the case in a chess tournament if one of the players decides to resort to threats and blackmail against their opponent.

If the Conflict is Reformulated, the process restarts from scratch: establish the Desired Outcomes, the starting Balance of Conflict, then start drawing cards.

A very common case of Conflict Reformulation is the fleeting alliance: wherever there are more than two parties involved, two of the parties may decide to temporarily join forces, with the Desired Outcome of getting rid of a third side. Of course, two sides who had temporarily joined forces may just as easily break their alliance.

Another common case is the Table deciding that the Conflict has lasted enough and that it is now either a stalemate or a victory. Again, if you are playing with a GM, the GM gets final say on this.

Thanks

- RpgGeek:

SteamCraft,adularia25,mawilson4,ctimmins - Reddit:

Salindurthas,Kaebl,bogglingsnog,matsmadison